A Richer Telling of United States History

By Courtney Ranaudo

This story originally appeared in the spring 2022 issue of Parker Magazine.

In March 2020, Parker social studies teachers sat down in their home-office chairs, met on Zoom, and deliberated over how to best teach the most essential curriculum to their students within the constraints brought on by the pandemic. They referred to their department’s scope and sequence guides, detailed documents created by Parker faculty that lay out specific learning targets and outcomes for each class. (See sidebar below)

As Grade 8 teachers culled through the U.S. History curriculum, they began to take note of some missing voices and perspectives.

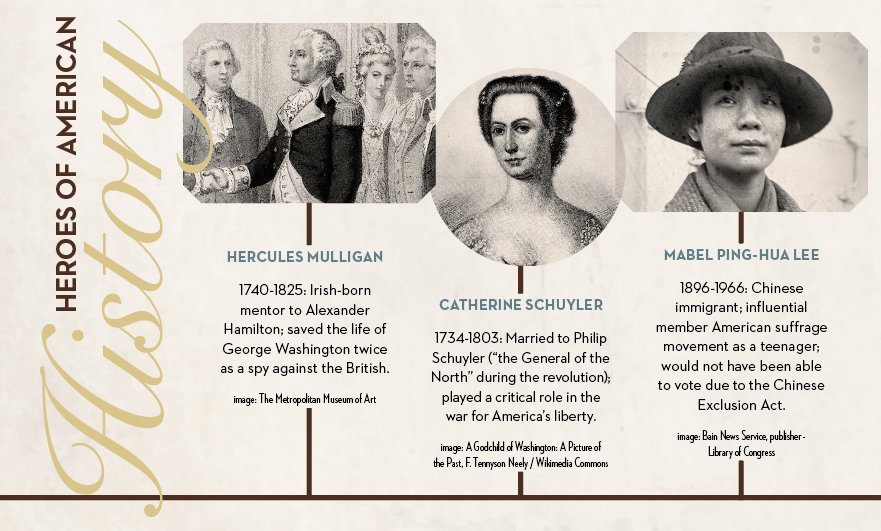

“We noticed, for instance, that the only female figure discussed during the American Revolution unit was Abigail Adams. That was it,” says Maggie Blyth, Grade 8 social studies teacher.

There was also a trend of minority ethnic groups only having the most difficult parts of their stories told. For example, the majority of discussion involving Indigenous Peoples was around the Trail of Tears. The only time Chinese American history was highlighted was during a brief lesson on the Chinese Exclusion Act.

“We needed to go deeper than just mentioning a group of people,” says Jeremy Howard, Grade 8 dean and social studies teacher. “And we wanted to see what happened when we started looking at them through a celebratory lens.”

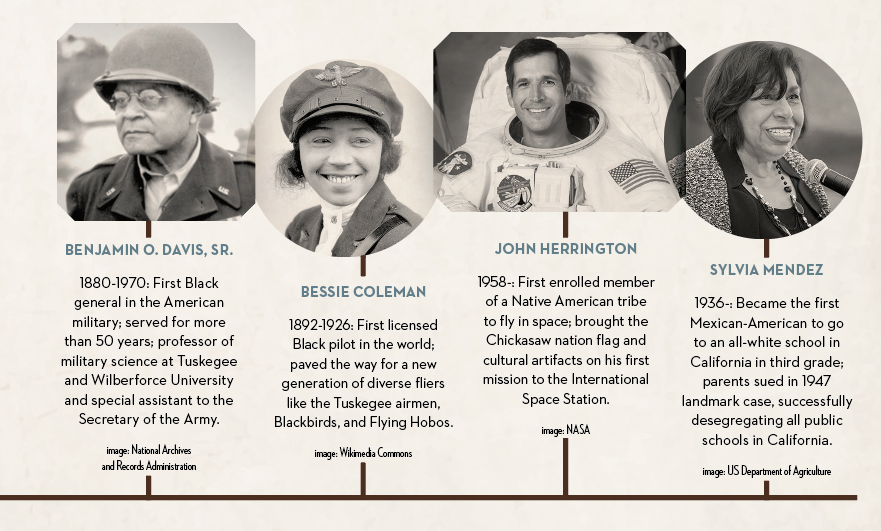

Once this philosophy was applied to the U.S. History curriculum, and new heroes and histories were added to the scope and sequence guide, faculty discovered a much richer telling of America’s story.

This led to the change of the course name from “U.S. History” to “Making Our Modern America.” As the curriculum evolved, there was a significant shift away from memorization and regurgitation of facts and toward a re-envisioning of everything that makes America what it is today: the psychology, the sociology, the geography, and the culture of the many identities that have shaped our country.

“When we look at the American Revolution unit,” notes Maggie, “We still talk about the Adamses, the Washingtons, and the Jeffersons. But now we incorporate the role that women played in the American Revolution, as well as the immigrant population, and people of color; all groups who were previously left out of the story. Which was so unfortunate, because without those people fighting and supporting the cause, the American Revolution would not have been successful.”

This approach also helps students form stronger connections between the history of eras long passed and the current events and communities they are familiar with today. When reflecting on the Chinese American experience, for instance, lessons were added to the curriculum highlighting the large Chinese immigrant population that came to California during the Gold Rush and the significant ways in which Chinatowns have impacted large cities like San Francisco and even San Diego throughout the last century.

Faculty also added a post-Civil War unit to the curriculum, which allowed them to celebrate the tremendous cultural impacts made by the African American community. “The African American story is so much more than enslavement and redlining,” says Maggie. “Now we also look at the great migration, the Harlem Renaissance, and the impact these events had on music, art, and culture in America. There’s so much joy in those stories.”

“It’s not about us feeling guilty about a group of people 100 years ago doing something; it’s about elevating the voices of the people who weren’t allowed to have a voice in it.”

A Students-First Approach

The most significant impact this updated curriculum has on Parker students is the volume of windows (opportunities to see something new in someone else’s experience) and mirrors (opportunities to see oneself and one’s own experience portrayed) it provides.

“We want to make sure that at some point, every child sitting in our classrooms can go, ‘Oh, cool, those people are like me, that’s like my family, that’s like my mom,’” says Maggie. “Whether it’s religion, race, ethnicity, or gender, it’s our task to ensure there’s a huge array of identities represented in the curriculum. It replicates the rich diversity of our country, and it’s our children that we’re trying to make feel known, because they are the center of all of this.”

While representing every identity and background within the curriculum may seem like an impossible feat, Parker teachers have creatively risen to the challenge.

“An important addition to our approach has been giving students more choice,” explains Jeremy. “We know there’s not enough time to do a deep dive on every immigrant group that’s come to the United States. So we give them things like choice boards, where we go out and try to find different identities that are representative of Parker. Students are given time to explore the choice board, so they can study a person or experience similar to their own identity or choose to learn about a new identity they’re unfamiliar with. Then, they start to make bigger connections, like how different cultural groups impacted one another, or major contributions from a group of people that can be seen today.”

The Good, the Bad, the Ugly, and Everything In-Between

Recent national attention on U.S. History curriculum has led to concerns and questions about how schools and teachers contend with the more challenging parts of America’s history and if lessons are being taught to shame particular groups of students.

Maggie and Jeremy directly address this issue with confidence, describing their own classrooms as spaces where students can ask questions and discuss difficult topics in developmentally appropriate ways.

In many ways, Jeremy says, the more contentious parts of American history have similarities to what students will face in their real lives. “The beauty of social studies is that it prepares us for the difficult conversations that should be had in our society. There are tough decisions to be made at every level of governance, and there are tough decisions to be made in a person’s own life and household.”

Jeremy notes that because Parker’s curriculum focuses on context within each lesson, students are well-practiced in asking questions instead of making rash judgments. “It’s easy to look back on history and say, ‘They should’ve done this, or shouldn’t have done that.’ But Parker students are always looking at what was going on at a point in time for certain decisions to be made.”

Maggie points out the contradiction that arises when students are asked to think critically while also ignoring large parts of American history. “If you don’t know the truth behind these topics—and more importantly, if you don’t have a safe place to practice thinking about these things and to ask questions like, ‘Why did this happen?’—then you’re not being prepared to become an independent thinker.”

“What we’re doing with this curriculum is simply looking at the fullest picture that we can provide,” Maggie continues. “That means discussing the good, the bad, the ugly, and everything in-between. It’s also elevating the people who historically have not been considered participants, even though many were actually the backbone of something significant within American history.”

When it comes to students’ feelings of shame or guilt when learning about challenging or upsetting historical events, Parker faculty and advisors make sure to hold space for those emotions and redirect them toward proactive awareness. “I actually had this conversation in advisory the other day,” says Jeremy. “I told my students, ‘There’s no need to feel guilty about this, it’s not something that I’m accusing you of doing, or you’re accusing me of doing; it’s something that happened.’ It’s not about us feeling guilty about a group of people 100 years ago doing something; it’s about elevating the voices of the people who weren’t allowed to have a voice in it. We are learning from societal mistakes and historical errors, not this idea of ‘you are bad’—and the kids totally get that.”

A Launching Pad for All Faculty

Within each course’s scope and sequence guide is a roadmap for how the class will be taught. It includes specifics about the major themes of the course, what materials will be used, the content students will learn, and how they’ll be assessed. Every year, typically during professional development time, Parker faculty within a particular subject meet to update the content within their scope and sequence as needed.

This year, Parker’s Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging (DEIB) team is working with Parker faculty in every subject to look at their curriculum through a similar lens as Grade 8 U.S. History. Using an Anti-Bias/Anti-Racist (ABAR) rubric, Parker faculty are now taking inventory of their own scope and sequence guides, ensuring the voices, experiences, history, and contributions of multiple identities—particularly Black and Indigenous people of color (BIPOC)—are ubiquitous.

By the end of the 2021-2022 school year, each course will have completed the ABAR audit. “When all subjects are identifying and addressing gaps and silences of BIPOC experiences, we honor the experiences represented in the Parker community, and help our students feel a true sense of belonging,” says Director of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging Christen Tedrow-Harrison.